Optimizing and measuring compile-time performance of pformat

07 Jun 2020As mentioned in my recent blog post, I wrote pformat a small formatting library with doesn’t try to be a general-purpose log library with all bells and whistles but one optimized for log messages.

std::string s = "foo {} bar"_fmt(10); // foo 10 bar

The main idea was to make it easy to use and compile-time checked. After my talk for Pure Storage Prague questions where asked about the compile-time performance.

In that blog post, I used the bloat test from the format-benchmark to measure it and the results were quite eye-opening.

This blog post looks at the improvements done and what the results are.

Step 0: Changing the build machine

I will later move to C++20 (for reasons that will become apparent later). I don’t have C++20 on my old MacBook. So, all new experiments are done on a machine with 4-core, i7 at 2.6 GHz, running Ubuntu 2004 using gcc-9.3:

Let’s repeat the measurements for calibration:

| Method | Compile Time, s | Compile Time, s (on old machine) |

|---|---|---|

| printf | 3.2 | 5.3 |

| printf+string | 24.5 | 47.6 |

| IOStreams | 33.2 | 95.1 |

| fmt | 37.0 | 74.9 |

| compiled_fmt | 37.2 | 66.0 |

| tinyformat | 75.3 | 136.3 |

| Boost Format | 244.4 | 353.4 |

| Folly Format | 261.4 | 380.4 |

| stb_sprintf | 3.7 | 6.9 |

| pformat | 69.5 | 130.0 |

The changes lie between roughly 1/3 (Folly Format) and 2/4 (IOstreams). I treat this as the new baseline

Step 1: Changing the experiment

In the last test, I used the bloat test script. However, I am not a fan of the experiment design.

The files are arbitrarily small. Just including

I propose changing the experiment to put more emphasis on the formatting compile-time than on the include files. Each translation unit now has 20 instead of 5 format statement, which 1 to 5 arguments. I am now also throwing one log message into the mix with has 10 format parameters. Why one and not 4 as with the other argument counts? My statistics over the Pure code base show that a larger number of arguments exist, but they are much rarer than 1-5 arguments.

Now, changing a benchmark in the middle is always suspicions, but stay with me. My argument is a) the change makes the benchmark more realistic and b) “my approach” looks relatively speaking, worse with the new benchmark. So, this wasn’t done to fudge the numbers.

I am open to a better benchmark. I would not base my PhD thesis on this benchmark to be honest, but it is what we have:

| Method | Compile Time, s | Compile Time, s (previous benchmark) |

|---|---|---|

| printf | 4.8 | 3.2 |

| printf+string | 28.7 | 24.5 |

| IOStreams | 41.9 | 33.2 |

| fmt | 47.5 | 37.0 |

| compiled_fmt | 58.7 | 37.2 |

| tinyformat | 94.0 | 75.3 |

| Boost Format | 337.2 | 244.4 |

| Folly Format | 349.3 | 261.4 |

| stb_sprintf | 5.5 | 3.7 |

| pformat | 140.7 | 69.5 |

The changes in the benchmark make a huge difference. Remember before, pformat was on par with tinyformat? Not anymore. The compile times of fmt, tinyformat, printf, stb_sprintf are pretty much constant. The changes in the number of log lines do not make a difference, but they make for format and may be folly. The design of the experiment matters.

pformat now looks much worse. It should be clear by now that the experiment wasn’t changed to make pformat look better.

Step 2: Removal of unnecessary includes

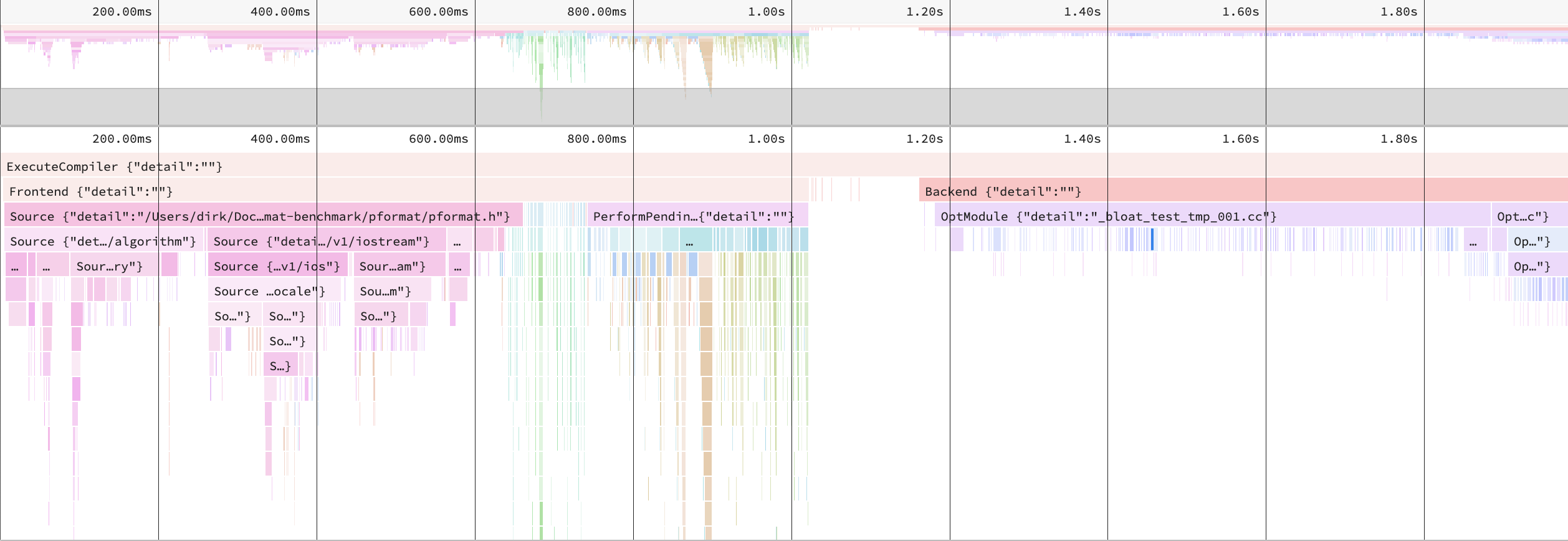

There does pformat spend the 294 seconds? Clang’s -ftime-trace can help.

We spend 1.9s on each translation unit. Around 650ms on includes, 350 ms on instantiations of functions (we see the recursive next calls in the graph). In the end, we spent 820 milliseconds on the backend.

Let’s tackle the easy task first: Removal of unnecessary includes. pformat has several unnecessary includes. I just didn’t check for them at all.

If we zoom into a single translation unit, this change reduces the include processing time to 400ms and the overall time to 1.7s.

I do not want to spend to much time here. There are no obviously unnecessary includes left. All header files which are left will be included by most files anyway, e.g. string_view. It is also not technically interesting.

Step 3: Get rid of recursive template instantiations

The big pain point and especially the pain point which doesn’t scale is the recursive template instantiation. So, the new design tries to keep the advantages of the original approach, but relies much less on template metaprogramming and uses constexpr functions instead.

The old approach tried to preserve as much information as possible into the type system. There is the type system for foo {} bar {} -> format_result<ref to str, format_element<0, 4>, format_parameter<0>, format_element<6, 10>,format_parameter>>.

This forced many template instantiations and they are not needed for performance.

We still want to do the parsing at compile-time and give the runtime/optimizer all or most information to work with, but now we are doing in normal variables. The format result type is now format_result<n> which n being the estimated number of format elements/format parameter pairs. Each format element now stores the start and end index in variables.

When we look at a translation unit in detail, we see that all the instantiations around 400-500ms. Each log messages instantiation takes between 2-4 ms. It appears that the time isn’t linear to the length of the log message. This indicates to me that the actual instantiation takes so much time and not so much the execution of the constexpr functions. No idea what clang is doing for 2-4 milliseconds. I am a software engineer of storage systems. In that time you can persistently perform around 10 IO operations. 4 milliseconds are a long time.

Anyway, the parsing is no longer the issue. We see between the 500-650ms timestamp all the format_to call. The runtime of each call is essentially Split up into the instantiation for forward_as_tuple and the visitors.

The good news is that these are no longer done per log message, but per log parameter type combination. The experiment is designed to have some reuse. Locking at the log messages in the Pure Storage code base, This appears to be a realistic assumption.

Step 4: Optimize format/visit function templates

The next major change is to get rid of the recursive template instantiation in the visit function, which is called when doing the actual formatting.

In C++, we have fold expressions, which compile much faster.

Here is an example of the code where we test if we can format all parameter types. The old code is:

template <typename type_t, typename... type_rest_t>

constexpr bool test_placements_helper() {

constexpr auto placeable = is_placeable<type_t>();

static_assert(placeable, "Type type_t not placeable");

if constexpr (!placeable) {

return false;

} else if constexpr (sizeof...(type_rest_t) == 0) {

return true;

} else {

return test_placements_helper<type_rest_t...>();

}

}

template <typename... type_t>

constexpr bool test_placements() {

if constexpr (sizeof...(type_t) == 0) {

return true;

} else {

return internal::test_placements_helper<type_t...>();

}

}

While this code uses C++17’s if constexpr, it completely ignored fold expressions as another important feature of C++17. The new code used that:

template <typename... type_t>

constexpr bool test_placements() {

return (internal::is_placeable<type_t>() && ...);

}

The code is shorter, much faster compilation (it appears that way at least) and, once you get used it, it much cleaner.

The main code used the following approach for concat together the output string from the format elements and format results:

auto t = std::forward_as_tuple(std::forward<args_t>(args)...);

parse_result_t::visit(

[this, &buf](auto fe) {

using placement::unsafe_place;

buf = unsafe_place(buf,

parse_result.str().data() + fe.start,

fe.size());

},

[&buf, &t](auto pe) {

using placement::unsafe_place;

auto const &arg = std::get<pe.index>(t);

buf = unsafe_place(buf, arg);

});

//[...]

template <typename element_func_t, typename parameter_func_t>

inline static constexpr void visit(element_func_t &&ev,

parameter_func_t &&pv) {

static_assert(is_valid_format_string());

visit_helper<element_func_t, parameter_func_t, element_t...>(

std::forward<element_func_t>(ev),

std::forward<parameter_func_t>(pv));

}

template <typename ev_t, typename pv_t, typename first_t,

typename... rest_t>

inline static constexpr void visit_helper(ev_t &&ev, pv_t &&pv) {

if constexpr (first_t::type == format_type::PARAMETER) {

pv(first_t{});

} else {

ev(first_t{});

}

visit_helper<ev_t, pv_t, rest_t...>(std::forward<ev_t>(ev),

std::forward<pv_t>(pv));

}

template <typename ev_t, typename pv_t>

inline static constexpr void visit_helper(ev_t &&, pv_t &&) {

return;

}

What took so long to compile were the visit_helper recursive templates themselves and the forward_as_tuple standard library call.

The new approach changes the order instead of iterating over the format_result entries and try to find the right argument from the tuple to format, it iterates over the arguments and finds the right format_result to place into the output string:

template <typename func_t,

typename... args_t>

inline constexpr void visit(func_t && func,

args_t &&... args) const {

if constexpr (sizeof...(args) == 0) {

func(string_view_of(results)));

} else {

auto result = results.begin();

auto visit_helper = [this, &result, &func](auto &&arg) {

if (!result->empty()) {

func(string_view_of(*result));

}

result++;

func(std::forward<decltype(arg)>(arg));

};

(visit_helper(args), ...);

if (!result->empty()) {

func(string_view_of(*result));

}

}

}

The parameter args are the arguments passed in by the caller to the format function.

We have to walk through the format element and call the ev lambda

For format elements and the pv lambda for the parameter. We call

The visit_helper as fold function, which maintains its state when to

call the lambdas.

That the format functions are still variadic template-based is unfortunate, but hardly avoidable. The design was meant so that any type with provides an unsafe_place function Can be called. So any variant or union or type identifier based approach is difficult. Maybe there are ways, but I don’t see that yet.

Step 5: Remove static asserts

The old code has many static asserts, which I used as compile-time unit tests. As much as I like the fast feedback, we should do that in each translation unit which Uses format. Instead, I moved them to extra translation units, which assert when the unit tests are built.

Where do these changes bring us?

| Method | Compile Time, s |

|---|---|

| printf | 4.8 |

| printf+string | 28.7 |

| IOStreams | 41.9 |

| fmt | 47.5 |

| compiled_fmt | 58.7 |

| tinyformat | 94.0 |

| Boost Format | 337.2 |

| Folly Format | 349.3 |

| stb_sprintf | 5.5 |

| pformat (orig) | 140.7 |

| pformat (changed) | 65.5 |

The changes really changed the picture. pformat compiles now faster than tinyformat and is seconds away (but still smaller than the compiled usage of fmt).

hana_format

While working on these changes, doing the measurements and writing this post, on May 25, Hana Dusikova posted an interesting Tweet with a link to godbolt.com proposing something similar using C++20 syntax:

Everything I wanted from std::format / fmt...https://t.co/vnq1ISSe1D@vzverovich

— Hana Dusíková 🍋 (@hankadusikova) May 25, 2020

Switching to gcc-10

I want to compare that code, which I call hana_format, with pformat and the other libraries:

Let’s do this step-by-step again. These are the results with gcc-10 and C++17 support.

| Method | Compile time, s | Compile Time, s (gcc-9.3) |

|---|---|---|

| printf | 4.8 | 4.8 |

| printf+string | 27.4 | 28.7 |

| IOStreams | 38.6 | 41.9 |

| fmt | 35.6 | 47.5 |

| compiled_fmt | 35.4 | 58.7 |

| tinyformat | 83.5 | 94.0 |

| Boost Format | 311.0 | 337.2 |

| Folly Format | 338.8 | 349.3 |

| stb_sprintf | 6.0 | 5.5 |

| pformat (changed) | 70.4 | 65.5 |

Most appear to be slightly faster (except pformat), but I will call it within the margin of error for now.

Switching to C++20

These are the results with gcc-10 for C++20.

| Method | Compile time, s | Compile Time, s (C++17) |

|---|---|---|

| printf | 4.2 | 4.8 |

| printf+string | 49.3 | 27.4 |

| IOStreams | 62.1 | 38.6 |

| fmt | 59.4 | 35.6 |

| compiled_fmt | 59.8 | 35.4 |

| tinyformat | 126.5 | 83.5 |

| Boost Format | XXXXX | 311.0 |

| Folly Format | 362.8 | 338.8 |

| stb_sprintf | 5.7 | 6.0 |

| pformat (changed) | 111.7 | 70.4 |

| hana_format | 187.0 |

First, Boost Format stopped compiling. I gave up at some point and removed it. It was strangely slow anyway.

Secondly, compilation times increased all over the board. Well, least for all C++ approaches. pformat from 70 seconds to 111 seconds, fmt from around 30 seconds to 60 seconds.

I can only speculate with hana_format is slower. This was very surprising. The code has a handwritten state machine to parse the grammar. In hana_format, the grammar takes a lambda to decide what to do with it, e.g. count the number of parameter or put characters into the output buffer. All in all the format string is parsed three times at compile-time.

In contrast, pformat does a quick guess at the beginning to get an upper bound on the number of format elements, then parses the grammar and puts it into the format results. When the output string is build these intermediate results are used instead of parsing the format string again. I suspect this difference will make up much of the difference.

I am still amazed how fast the the fmt library is.

Runtime performance

Compile-time was one element, but the three pillars of pformat were compile-time checking, extensibility and performance.

To finish this up, let’s look at runtime performance. pformat as a benchmark, which formats the string “foo {} bar {} do {}” with three arguments (int, int, const char *) into a char buffer.

BM_Fmt/1 67.3 ns 67.3 ns 8767537

BM_Fmt/8 554 ns 554 ns 1181495

BM_Fmt/16 1105 ns 1105 ns 588740

BM_PFormat/1 28.3 ns 28.3 ns 25217923

BM_PFormat/8 167 ns 166 ns 4065018

BM_PFormat/16 313 ns 312 ns 2185588

BM_Printf/1 146 ns 146 ns 4622225

BM_Printf/8 1172 ns 1172 ns 544738

BM_Printf/16 2437 ns 2437 ns 280527

BM_Cout/1 656 ns 656 ns 898703

BM_Cout/8 5263 ns 5262 ns 116334

BM_Cout/16 10423 ns 10423 ns 61579

BM_HanaFormat/1 37.2 ns 37.2 ns 18261944

BM_HanaFormat/8 315 ns 315 ns 2182267

BM_HanaFormat/16 638 ns 638 ns 965965

Compared to the earlier results, pformat is now a bit slower. Looking at the assembly still shows that the optimizer can make sense out of the information, which has been computed at compile-time and generates quite good code, but there is a bit more noise then before. It isn’t ideal anymore.

However, it is still faster than fmt and effectively even then hana_format. The latter is so surprising because both the assembly of both look well optimized. The results are so close, I would account that as measurement errors.

Compared to an approach which incurred way to high a cost at compile-time, this is likely a price worth paying.

With three ideas, I improved the compile-time of pformat about around 50%.

- Carefully look at the included files. I usually would be wary of not using some standard tools like string_view in the hope to improving compile-times, but maybe there are cases were every ms counts and one has to assume that e.g. string_view not be included at all.

- Avoid unnecessary template instantiations. Especially recursive template instantiations.

- Use fold expressions as they appear to be much faster to compile. This is likely because the compile doesn’t have to instantiate all the templates to do so.

This journey shows my fallacy to run to extensive template meta programming when I should have trusted the compiler trusted modern C++ and using constexpr and let the compiler do its job.

The new code can be found in the lesstemplate branch of pformat. I will likely clean that up a bit more and push it to master soon.

I never worked with compile-time programming before pformat. It was an experiment if something like that is possible. And I never looked into compile-time programming. Usually, this is treated as a problem I can solve with hardware. However, if your algorithm is quadratic, this becomes expensive very fast and after some point even impossible to do.

Also, the time-trace tool in clang is very helpful to make compile-time improvements engineering work and not guesswork.