07 Jun 2020

As mentioned in my recent blog post, I wrote pformat a small formatting library with doesn’t try to be a general-purpose log library with all bells and whistles but one optimized for log messages.

std::string s = "foo {} bar"_fmt(10); // foo 10 bar

The main idea was to make it easy to use and compile-time checked. After my talk for Pure Storage Prague questions where asked about the compile-time performance.

In that blog post, I used the bloat test from the format-benchmark to measure it and the results were quite eye-opening.

This blog post looks at the improvements done and what the results are.

Step 0: Changing the build machine

I will later move to C++20 (for reasons that will become apparent later). I don’t have C++20 on my old MacBook. So, all new experiments are done on a machine with 4-core, i7 at 2.6 GHz, running Ubuntu 2004 using gcc-9.3:

Let’s repeat the measurements for calibration:

| Method |

Compile Time, s |

Compile Time, s (on old machine) |

| printf |

3.2 |

5.3 |

| printf+string |

24.5 |

47.6 |

| IOStreams |

33.2 |

95.1 |

| fmt |

37.0 |

74.9 |

| compiled_fmt |

37.2 |

66.0 |

| tinyformat |

75.3 |

136.3 |

| Boost Format |

244.4 |

353.4 |

| Folly Format |

261.4 |

380.4 |

| stb_sprintf |

3.7 |

6.9 |

| pformat |

69.5 |

130.0 |

The changes lie between roughly 1/3 (Folly Format) and 2/4 (IOstreams).

I treat this as the new baseline

Step 1: Changing the experiment

In the last test, I used the bloat test script. However, I am not a fan of the experiment design.

The files are arbitrarily small. Just including changes the results

in a meaningful way. Now, files like or will be included in many or most source files.

We pay the cost for including them using one of the libraries or not.

I propose changing the experiment to put more emphasis on the formatting compile-time than on the include files. Each translation unit now has 20 instead of 5 format statement, which 1 to 5 arguments.

I am now also throwing one log message into the mix with has 10 format parameters. Why one and not 4 as with the other argument counts? My statistics over the Pure code base show that a larger number of arguments exist, but they are much rarer than 1-5 arguments.

Now, changing a benchmark in the middle is always suspicions, but stay with me.

My argument is a) the change makes the benchmark more realistic

and b) “my approach” looks relatively speaking, worse with the new benchmark.

So, this wasn’t done to fudge the numbers.

I am open to a better benchmark. I would not base my PhD thesis on

this benchmark to be honest, but it is what we have:

| Method |

Compile Time, s |

Compile Time, s (previous benchmark) |

| printf |

4.8 |

3.2 |

| printf+string |

28.7 |

24.5 |

| IOStreams |

41.9 |

33.2 |

| fmt |

47.5 |

37.0 |

| compiled_fmt |

58.7 |

37.2 |

| tinyformat |

94.0 |

75.3 |

| Boost Format |

337.2 |

244.4 |

| Folly Format |

349.3 |

261.4 |

| stb_sprintf |

5.5 |

3.7 |

| pformat |

140.7 |

69.5 |

The changes in the benchmark make a huge difference. Remember before, pformat was on par with tinyformat? Not anymore.

The compile times of fmt, tinyformat, printf, stb_sprintf are pretty much constant. The changes in the number of log lines do not make a difference, but they make for format and may be folly. The design of the experiment matters.

pformat now looks much worse. It should be clear by now that the experiment

wasn’t changed to make pformat look better.

Step 2: Removal of unnecessary includes

There does pformat spend the 294 seconds?

Clang’s -ftime-trace can help.

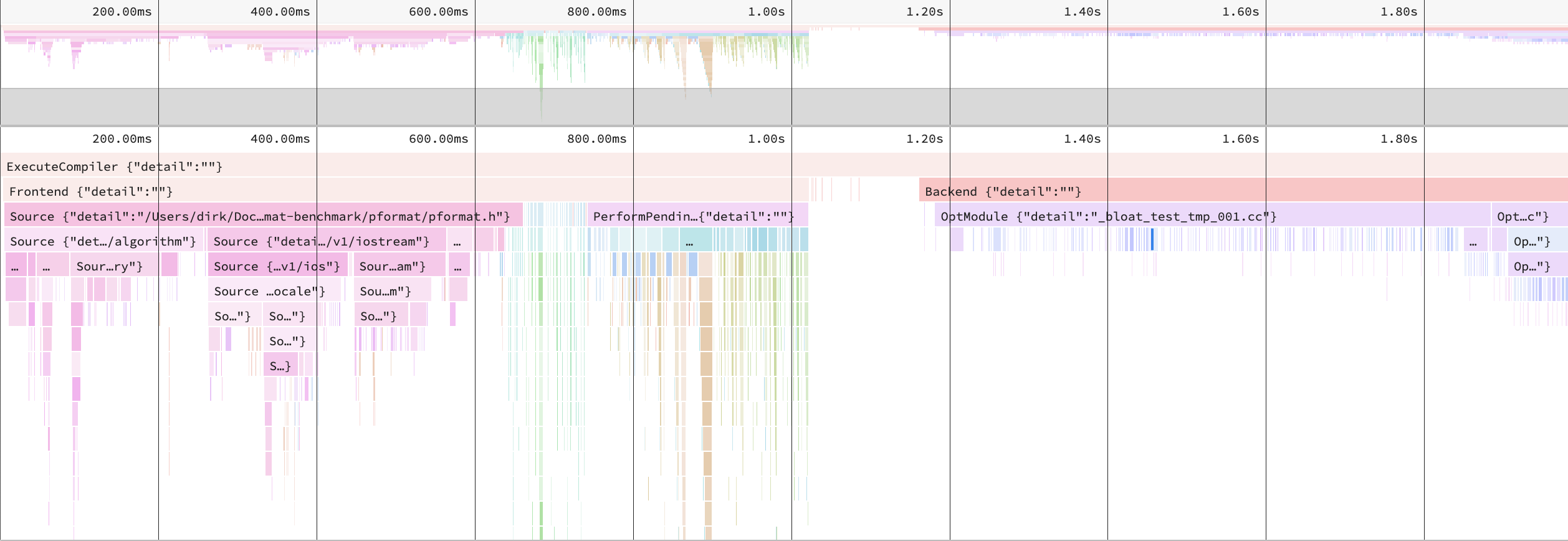

We spend 1.9s on each translation unit. Around 650ms on includes, 350 ms on instantiations of functions (we see the recursive next calls in the graph). In the end, we spent 820 milliseconds on the backend.

Let’s tackle the easy task first: Removal of unnecessary includes. pformat has several unnecessary includes. I just didn’t check for them at all.

If we zoom into a single translation unit, this change reduces the include processing time to 400ms and the overall time to 1.7s.

I do not want to spend to much time here. There are no obviously unnecessary includes left. All header files which are left will be included by most files anyway, e.g. string_view. It is also not technically interesting.

Step 3: Get rid of recursive template instantiations

The big pain point and especially the pain point which doesn’t scale is the recursive template instantiation.

So, the new design tries to keep the advantages of the original approach, but relies much less on template metaprogramming and uses constexpr functions instead.

The old approach tried to preserve as much information as possible into the type system. There is the type system for foo {} bar {} -> format_result<ref to str, format_element<0, 4>, format_parameter<0>, format_element<6, 10>,format_parameter>>.

This forced many template instantiations and they are not needed for performance.

We still want to do the parsing at compile-time and give the runtime/optimizer all or most information to work with, but now we are doing in normal variables. The format result type is now format_result<n> which n being the estimated number of format elements/format parameter pairs. Each format element now stores the start and end index in variables.

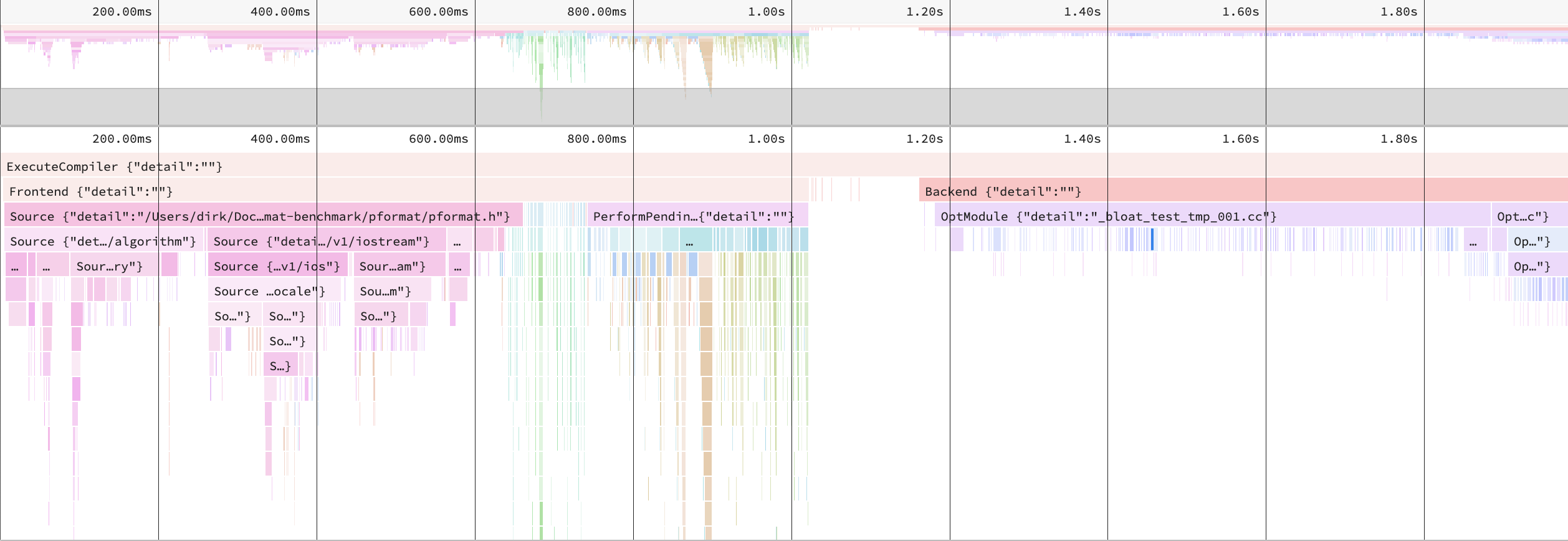

When we look at a translation unit in detail, we see that all the instantiations around

400-500ms. Each log messages instantiation takes between 2-4 ms. It appears that the time isn’t linear to the length of the log message. This indicates to me that

the actual instantiation takes so much time and not so much the execution of the

constexpr functions. No idea what clang is doing for 2-4 milliseconds. I am

a software engineer of storage systems. In that time you can persistently perform around 10 IO operations. 4 milliseconds are a long time.

Anyway, the parsing is no longer the issue. We see between the 500-650ms

timestamp all the format_to call. The runtime of each call is essentially

Split up into the instantiation for forward_as_tuple and the visitors.

The good news is that these are no longer done per log message, but

per log parameter type combination. The experiment is designed to have some reuse. Locking at the log messages in the Pure Storage code base,

This appears to be a realistic assumption.

The next major change is to get rid of the recursive template instantiation in the visit function, which is called when doing the actual formatting.

In C++, we have fold expressions, which compile much faster.

Here is an example of the code where we test if we can format all parameter types.

The old code is:

template <typename type_t, typename... type_rest_t>

constexpr bool test_placements_helper() {

constexpr auto placeable = is_placeable<type_t>();

static_assert(placeable, "Type type_t not placeable");

if constexpr (!placeable) {

return false;

} else if constexpr (sizeof...(type_rest_t) == 0) {

return true;

} else {

return test_placements_helper<type_rest_t...>();

}

}

template <typename... type_t>

constexpr bool test_placements() {

if constexpr (sizeof...(type_t) == 0) {

return true;

} else {

return internal::test_placements_helper<type_t...>();

}

}

While this code uses C++17’s if constexpr, it completely ignored

fold expressions as another important feature of C++17. The new

code used that:

template <typename... type_t>

constexpr bool test_placements() {

return (internal::is_placeable<type_t>() && ...);

}

The code is shorter, much faster compilation (it appears that way at least) and, once you get used it, it much cleaner.

The main code used the following approach for concat together the output

string from the format elements and format results:

auto t = std::forward_as_tuple(std::forward<args_t>(args)...);

parse_result_t::visit(

[this, &buf](auto fe) {

using placement::unsafe_place;

buf = unsafe_place(buf,

parse_result.str().data() + fe.start,

fe.size());

},

[&buf, &t](auto pe) {

using placement::unsafe_place;

auto const &arg = std::get<pe.index>(t);

buf = unsafe_place(buf, arg);

});

//[...]

template <typename element_func_t, typename parameter_func_t>

inline static constexpr void visit(element_func_t &&ev,

parameter_func_t &&pv) {

static_assert(is_valid_format_string());

visit_helper<element_func_t, parameter_func_t, element_t...>(

std::forward<element_func_t>(ev),

std::forward<parameter_func_t>(pv));

}

template <typename ev_t, typename pv_t, typename first_t,

typename... rest_t>

inline static constexpr void visit_helper(ev_t &&ev, pv_t &&pv) {

if constexpr (first_t::type == format_type::PARAMETER) {

pv(first_t{});

} else {

ev(first_t{});

}

visit_helper<ev_t, pv_t, rest_t...>(std::forward<ev_t>(ev),

std::forward<pv_t>(pv));

}

template <typename ev_t, typename pv_t>

inline static constexpr void visit_helper(ev_t &&, pv_t &&) {

return;

}

What took so long to compile were the visit_helper recursive

templates themselves and the forward_as_tuple standard library call.

The new approach changes the order instead of iterating over the

format_result entries and try to find the right argument from the tuple

to format, it iterates over the arguments and finds the right format_result

to place into the output string:

template <typename func_t,

typename... args_t>

inline constexpr void visit(func_t && func,

args_t &&... args) const {

if constexpr (sizeof...(args) == 0) {

func(string_view_of(results)));

} else {

auto result = results.begin();

auto visit_helper = [this, &result, &func](auto &&arg) {

if (!result->empty()) {

func(string_view_of(*result));

}

result++;

func(std::forward<decltype(arg)>(arg));

};

(visit_helper(args), ...);

if (!result->empty()) {

func(string_view_of(*result));

}

}

}

The parameter args are the arguments passed in by the caller to the format function.

We have to walk through the format element and call the ev lambda

For format elements and the pv lambda for the parameter. We call

The visit_helper as fold function, which maintains its state when to

call the lambdas.

That the format functions are still variadic template-based is unfortunate, but hardly

avoidable. The design was meant so that any type with provides an unsafe_place function

Can be called. So any variant or union or type identifier based approach is difficult. Maybe there are ways, but I don’t see that yet.

Step 5: Remove static asserts

The old code has many static asserts, which I used as compile-time unit tests.

As much as I like the fast feedback, we should do that in each translation unit which

Uses format. Instead, I moved them to extra translation units, which assert when the unit tests are built.

Where do these changes bring us?

| Method |

Compile Time, s |

| printf |

4.8 |

| printf+string |

28.7 |

| IOStreams |

41.9 |

| fmt |

47.5 |

| compiled_fmt |

58.7 |

| tinyformat |

94.0 |

| Boost Format |

337.2 |

| Folly Format |

349.3 |

| stb_sprintf |

5.5 |

| pformat (orig) |

140.7 |

| pformat (changed) |

65.5 |

The changes really changed the picture.

pformat compiles now faster than tinyformat and is seconds

away (but still smaller than the compiled usage of fmt).

While working on these changes, doing the measurements and writing this post,

on May 25, Hana Dusikova posted an interesting Tweet with a link to

godbolt.com proposing something similar using C++20 syntax:

Switching to gcc-10

I want to compare that code, which I call hana_format, with pformat

and the other libraries:

Let’s do this step-by-step again. These are the results with gcc-10 and C++17 support.

| Method |

Compile time, s |

Compile Time, s (gcc-9.3) |

| printf |

4.8 |

4.8 |

| printf+string |

27.4 |

28.7 |

| IOStreams |

38.6 |

41.9 |

| fmt |

35.6 |

47.5 |

| compiled_fmt |

35.4 |

58.7 |

| tinyformat |

83.5 |

94.0 |

| Boost Format |

311.0 |

337.2 |

| Folly Format |

338.8 |

349.3 |

| stb_sprintf |

6.0 |

5.5 |

| pformat (changed) |

70.4 |

65.5 |

Most appear to be slightly faster (except pformat), but I will call

it within the margin of error for now.

Switching to C++20

These are the results with gcc-10 for C++20.

| Method |

Compile time, s |

Compile Time, s (C++17) |

| printf |

4.2 |

4.8 |

| printf+string |

49.3 |

27.4 |

| IOStreams |

62.1 |

38.6 |

| fmt |

59.4 |

35.6 |

| compiled_fmt |

59.8 |

35.4 |

| tinyformat |

126.5 |

83.5 |

| Boost Format |

XXXXX |

311.0 |

| Folly Format |

362.8 |

338.8 |

| stb_sprintf |

5.7 |

6.0 |

| pformat (changed) |

111.7 |

70.4 |

| hana_format |

187.0 |

|

First, Boost Format stopped compiling. I gave up at some point

and removed it. It was strangely slow anyway.

Secondly, compilation times increased all over the board. Well,

least for all C++ approaches. pformat from 70 seconds to 111 seconds, fmt from around 30 seconds to 60 seconds.

I can only speculate with hana_format is slower. This was very surprising.

The code has a handwritten state machine to parse the grammar. In hana_format,

the grammar takes a lambda to decide what to do with it, e.g. count the number of parameter or put characters into the output buffer. All in all the format string is parsed three times at compile-time.

In contrast, pformat does a quick guess at the beginning to get an upper bound on the number of format elements, then parses the grammar and puts it into the format results. When the output string is build these intermediate results are used instead of parsing the format string again. I suspect this difference will make up much of the difference.

I am still amazed how fast the the fmt library is.

Compile-time was one element, but the three pillars of

pformat were compile-time checking, extensibility and performance.

To finish this up, let’s look at runtime performance. pformat

as a benchmark, which formats the string “foo {} bar {} do {}” with

three arguments (int, int, const char *) into a char buffer.

BM_Fmt/1 67.3 ns 67.3 ns 8767537

BM_Fmt/8 554 ns 554 ns 1181495

BM_Fmt/16 1105 ns 1105 ns 588740

BM_PFormat/1 28.3 ns 28.3 ns 25217923

BM_PFormat/8 167 ns 166 ns 4065018

BM_PFormat/16 313 ns 312 ns 2185588

BM_Printf/1 146 ns 146 ns 4622225

BM_Printf/8 1172 ns 1172 ns 544738

BM_Printf/16 2437 ns 2437 ns 280527

BM_Cout/1 656 ns 656 ns 898703

BM_Cout/8 5263 ns 5262 ns 116334

BM_Cout/16 10423 ns 10423 ns 61579

BM_HanaFormat/1 37.2 ns 37.2 ns 18261944

BM_HanaFormat/8 315 ns 315 ns 2182267

BM_HanaFormat/16 638 ns 638 ns 965965

Compared to the earlier results, pformat is now a bit slower.

Looking at the assembly still shows that the optimizer

can make sense out of the information, which has

been computed at compile-time and generates quite good code,

but there is a bit more noise then before. It isn’t ideal anymore.

However, it is still faster than fmt and effectively even then

hana_format. The latter is so surprising because both the assembly of both

look well optimized. The results are so close, I would account that as measurement

errors.

Compared to an approach which incurred way to high a cost at compile-time,

this is likely a price worth paying.

With three ideas, I improved the compile-time of pformat

about around 50%.

- Carefully look at the included files. I usually would be wary

of not using some standard tools like string_view in the hope to

improving compile-times, but maybe there are cases were every ms counts

and one has to assume that e.g. string_view not be included at all.

- Avoid unnecessary template instantiations. Especially recursive template

instantiations.

- Use fold expressions as they appear to be much faster to compile. This is likely

because the compile doesn’t have to instantiate all the templates to do so.

This journey shows my fallacy to run to extensive template meta programming

when I should have trusted the compiler trusted modern C++ and using

constexpr and let the compiler do its job.

The new code can be found in the lesstemplate branch of pformat. I will

likely clean that up a bit more and push it to master soon.

I never worked with compile-time programming before pformat. It was an

experiment if something like that is possible. And I never looked into

compile-time programming. Usually, this is treated as a problem I

can solve with hardware. However, if your algorithm is quadratic, this

becomes expensive very fast and after some point even impossible to do.

Also, the time-trace tool in clang is very helpful to make compile-time

improvements engineering work and not guesswork.

25 May 2020

One of my favorite books is “Effective Java” by Joshua Bloch.

I am a Java developer by training who just happen to have landed in infrastructure and systems programming.

I am mostly using Modern C++ at this point. It is still my favorite book. It contains 90 guidelines on how to use the Java language well.

My theory is that C++ developers should read effective Java. Thus, the clickbait title. It is the missing book for C++.

A couple of years ago I was leading a team of college new grads. In college, you learn two things: Computer Science and Coding. However, they are not really learning software engineering: How to write software which can stand the test of time. Neither is that a reasonable expectation from a college. CS is the foundation for all of what we write and the cleanest, most maintainable code is useless if the code is wrong or the algorithm is way off. Back then, I was preparing a reading list for these new C++ engineers. The obvious books were on the reading list like Effective Modern C++, but also Effective Java.

I will make the case in two steps:

My reasoning is that most tips in Effective Java (EJ), with some imagination, apply also to C++. I will revisit all 90 items of Effective Java and discuss how and if they apply to C++. Some will apply with some modifications, some will not apply at all. I will rate each item on a scale of ‘1’ to ‘5’ with ‘5’ meaning directly applies to C++ with ‘1’ meaning does not apply to C++.

But I go further: Many tips apply to C++ and there is no other comparable guideline document specialized on C++. There are three sources of guidelines I will consider: Effective Modern C++ (EMC), Effective C++ (EC) and the C++ core guidelines. Effective C++ and Effective Modern C++ are books quite comparable to Effective Java in approach and size.

On the other hand, there are hundreds of Core Guidelines. I personally would wish sometimes that they reflect a bit more on the word “core”. My theory is that most C++ guidelines are so focused on the low-level details like xvalue references that some of the more important high-level discussions do not take place. The quality of the text of guidelines also differs very much. Some have good explanations and examples, why others are only the title and a TODO, e.g. the CP.201.

Chapter 2: Creating and Destroying Objects

Well, we create objects and destroy objects in C++ and Java. However, we do it in different ways with C++ using the creation on the stack as the default.

In Java, we always use new:

List<String> arrayNames = new ArrayList<>();

the equivalent code in C++ is one of these depending on the situation:

std::vector<string> array_names;

auto array_names = std::make_unique<vector<string>>();

Item 1: Consider static factory methods instead of constructors

[5/5] Factory methods appears to be quite uncommon in C++, but the argumentation applies 100%. With return value optimization, there isn’t even much extra overhead associated with it. Effective Modern C++ doesn’t mention factories. Effective C++ mentions factories but doesn’t appear to discuss when and why to use them. A subset of what is covered in Item 1 is also covered by C.50. While I do not consider Abseils TotW in this article, it is interesting that TotW 42 is a match.

Item 2: Consider a builder when faced with many constructors

[5/5] In my view, the argument applies 100% for C++. A constructor with many elements is as bad in C++ as it is in Java. Neither the EC or EMC books nor the core guidelines do not talk about the builder pattern.

This article gives the builder pattern 3 out of 4 stars for popularity in C++ and while the motivation is correct never ever write the code as given in that article.

Item 3: Enforce the singleton property with a private constructor or enum type

[3/5] Avoid singletons and obviously, the enum trick doesn’t work in C++, but if you want a singleton, make the constructor private applies to 100%. I.3 correctly says “Avoid singletons”, but it doesn’t talk about how to do it if needed.

Item 4: Enforce non-instantiability with a private constructor

[1/5] The usage is actually quite different in Java and C++. In Java, there are a lot of non-instantiable classes like Objects because we need to put static methods on something. C++ still has a lot of classes for which we never expect an instance, but I have never seen the instantiation of such an object to be prohibited. For example, the std::is_same struct can be instantiated. Maybe it would be a good idea to make clearer which classes are supposed to have instances and which are not, but it does not appear to be done.

Item 5: Prefer dependency injection to hardwiring resources

[5/5] Applies to 100%. I cannot find any core guideline about it. At Pure, we have a nice system for this.

Item 6: Avoid creating unnecessary objects

[3/5] Here, we have a tip where the common practice differs materially. Sure, even in C++ you are wary of the unnecessary creation of temporary objects, but in general, this isn’t so much an issue in C++. Somewhat surprisingly I didn’t find a core guideline tip about temporary objects at all.

There is a reading in which there is more similarity. Unnecessary objects are discouraged because Java allocation and GC overhead they are causing. In some sense, that is true in C++ for heap-allocated objects, which are often overused.

Item 7: Eliminate obsolete object references

[2/5] In C++ we think much more about object lifetimes, so many this is obvious to a C++ developer, but just a couple of weeks ago I had to read the code of a hand-written container class (where std::vector should just have been used) which didn’t call the destructor on clear().

Item 8: Avoid finalizers and cleaners

[1/5] I would give -1 out of 5 if that would be possible. That is exactly what you do in C++ thanks to the clear object lifetime guarantees. Object lifetime is a topic where Java really annoys me. I think core guideline C.30 is the closed match in the core guideline which proves the opposite.

4 out of 8 tips for Java mostly apply to C++.

Chapter 3: Methods Common to All Objects

This is interesting as there are no methods in C++ which are common to all objects.

All Java objects inherit from java.lang.Object, which has functions like

equals and hashCode, but also a build-in condition variable/lock with wait/notify.

Item 9: Prefer try-with-resources to try-finally

[4/5] I want to rephrase that to use “RAII instead of try-finally” for C++. So it kind of applies just in a different (better) way. R.1 is the matching core guideline.

Item 10: Obey the general contract when overriding equals

[4/5] Rephrased for C++ as “Obey the general contract when providing an == or < operator”, this still applies. Even the contracts are the same. C.160 (“Define operators primarily to mimic conventional usage”) is similar, but much less explicit about the requirements. What the contract actually is is not mentioned at all, while Item 10 goes into quite a detail on how to write a good equals method. I actually see a number

of == implementations, which are not really implementing the contract.

Item 11: Always override hashcode when you override equals

[4/5] Again, this needs to be rephrased a bit. If you provide a hash function it better matches the == and < operators. But there is no need in C++ to always provide a hash function just because == or < is available. This is a weirdness of Java. However, the core guidelines do not mention that == and any hash overload should match up in a certain way. This is an important guideline has it can lead to subtle bugs if == and std::hash do not match up.

Abseil’s tip 152 talks about Abseil’s approach

on hash code and how to test that the hash code matches operator==.

Item 12: Always override toString()

[1/5] The equivalent would to always provide an operator<< method, I guess. Nobody does that.

Item 13: Override clone judiciously

[1/5] An interesting difference between Java and C++. The equivalent of clone is

the copy/move constructor and assignment operator and they come with ever object unless

you opt-out. In Java, you have to implement the Clonable interface. If the interface is implemented, the default implementation of clone copies all the field in a shallow copy, which matches C++’s behavior if e.g. a class contains a shared_ptr member, but

it doesn’t match for embedded members.

Item 14: Consider implementing Comparable

[4/5] Again rephrased to “Consider implementing < operator”, I think this can stand. The cpp core guidelines talk a lot about the operators, e.g. details like returning *this, but not if and when to implement them.

4 out of 6 tips for Java apply mostly also to C++.

Chapter 4: Classes and Interfaces

C++ and Java both have classes. C++ doesn’t have a concept called

interface, but it has abstract classes.

Item 15: Minimize the accessibility of classes and members.

[4/5] Both are true but in different ways. For members, the rules are the same with private and protected. However, C++ doesn’t have private classes as a language construct. However, if a class is an implementation detail consider not putting it into a header file. Core guideline C.9 is the closed match.

Item 16: In public classes, use accessor methods, not public fields

[?/5] I am not even sure what the standard way in C++ here is, but it doesn’t appear to be done as a matter of guidelines. While C.9 has a setter and a getter, there is also C.131 which explicitly says to not have accessor methods. It would be helpful if the core guidelines would be consistent.

In general, getters and setters are not great class design in Java and C++.

The urge to just expose every field with getters and setters is a remarkable

predicator for more inexperienced Java programmers.

Item 17: Minimize mutability

[3/5] This is an interesting topic. Java tries to share objects references freely, but minimize mutability.

class MyObject {

private final SomeOtherObject someOtherObject;

MyObject(SomeOtherObject o) {

this.someOtherObject = o;

}

}

C++ has a different approach. In C++ we use value semantics and we have mutable objects, but they are not shared references, but independent copies. However, for shared objects making references const when needed is good practice. Making members const when possible is good practice. They solve a similar problem in slightly different ways. There is a complete section of the core guidelines about mutability.

Item 18: Favor composition over inheritance

[5/5] yes, yes, yes. Same arguments. I think this is one of the most important items for Java and C++ in this collection of tips and the cpp core guidelines do not mention it. The closed you get is C.129 “When designing a class hierarchy, distinguish between implementation inheritance and interface inheritance

“, but it is not the same. I feel something is missing here in the guidelines for C++. Effective C++’s Item 32 “Make sure public inheritance models ‘is-a’” comes very close.

Item 19: Design and document for inheritance or else prohibit it

[4/5] The arguments still applies to the letter. However, we have to do more work in C++ to prohibit it. We have to mark each virtual function final. You can still subclass, but you can no longer do any damage to it. C.139 argues explicitly against this item. I believe in the argument of Effective Java more than in the argument of C.139.

Item 20: Prefer interfaces to abstract classes

[2/5] Clearly, this means something very concrete in Java, while the syntactic difference doesn’t exist in C++. C.129, which I already mentioned for Item 18 defines the term interface for C++ and captures essentially this item. Neither the EMC book or nor the EC book capture.

Item 21: Design interfaces for posterity

[5/5] The issue exists in C++. The literal tip mostly applies 1:1. However, the situation is much worse in C++. The ABI is much stricter in C++ than in Java. A jar file containing a class file can be used as long as there is no incompatible change in the method. In C++, the methods are the ABI, but also the fields and other details.

C++ feels it is unable to fix unordered_map or the regular expression engine due to ABI issues. For example, in Java 8 the data structure for collision resolution has been changed from a linked list to a balanced tree (see link. That isn’t possible without major pain in C++.

Item 22: Use interfaces only to define types

[1/5] Does not apply to C++.

Item 23: Prefer class hierarchies to tagged classes

[2/5] Tagged classes are also bad design in C++. However, class hierarchies mean dynamic dispatching and usually mean dynamic allocation. Both things we are wary about. With std::variant we have kind of an alternative tool, while I would argue should be preferred to tagged classes in C++. I can not find a core guideline talking about this topic. Given the design space involving std::variant and class hierarchies, a guideline is overdue.

Item 24: Prefer static member classes over nonstatic

[1/5] This is cheating as C++ only has the equivalent of non-static member classes.

Item 25: Limit source files to a single top-level class

[1/5] There are different approaches to physical design in C++. Some people just put a class in a header and have a header and source file with matching names in a lot of ways mirroring the Java approach recommended here. Others don’t do that. Pure certainly doesn’t. The SF section of the core guidelines talk about physical design, but it doesn’t mention this. The Bloomberg guidelines are one of the stricter guidelines on the physical design and they mention a h/cpp file per component, not per class.

4 out of 11 tips mostly apply to C++, too. Considering this chapter was about classes, I was surprised how low the ratio was compared to other sections.

Chapter 5: Generics

This chapter will mostly not apply to C++ as generics and templates look similar in a first syntactic look, but they are mostly nothing alike.

Item 26: Don’t use raw types

[1/5] However, this is again cheating as this is not possible in C++, to begin with. You cannot construct a vector without providing the type of values in the vector. I have to rant for a second. Generics were introduced into the language in Java 5, 16 years ago. There is no excuse to write raw types.

I guess std::any is effectively like raw types. We will if that addition to C++17 will blow up in our faces at some point.

Item 27: Eliminate unchecked warnings

[1/5] This does not apply

Item 28: Prefer lists to arrays

[5/5] This again needs a little rephrasing: “Prefer collection classes to raw arrays”. List in Java just means an ordered collection of objects and is not equivalent to std::list (which would be java.lang.LinkedList). Actually, there is no equivalent to the concept of a collection in C++.

This guideline holds for C++. Surprisingly, the core guidelines don’t mention this. The closed item is ES.27, but it is way less general.

Item 29: Favor generic types

[1/5] Does not apply

Item 30: Favor generic methods

[1/5] Does not apply

Item 31: use bounded wildcards to increase API flexibility

[1/5] Does not apply. Interesting concept. Maybe the same thing can be done with lot of SFINAE.

Item 32: Combine generics and varargs judiciously

[1/5] Does not apply to C++. Varargs in Java is similar to initializer lists in C++. However, varargs are implemented with raw arrays in Java, which do not play well with generics for annoying technical reasons.

Item 33: Consider typesafe heterogeneous containers

[5/5] The article describes a hacky workaround to std::any. The alternative in the C++ world to an API which just stores a java.lang.Object instance with heavy casting would be a void * with heavy casting. Casting is frowned upon in both languages. There is no cpp core guideline about when to use std::any.

2 out of 8 apply.

Chapter 6: Enums and Annotations

Enums are much nicer to use in Java than in C++. Oh, I miss Java enums. However, mostly this chapter will not apply to C++ beyond the basics.

Item 34: Use enums instead of int constants

[5/5] True, no discussion. This is covered in Enum.1 of the core guidelines.

Item 35: Use instance fields instead of ordinals

[1/5] Enums don’t have instance fields in C++. We only have the ordinals aka casting an enum to its underlying type. So this guideline does not apply to C++.

Item 36: use EnumSet instead of bit fields

[1/5] C++ doesn’t have the equivalent to EnumSet in the standard. So this doesn’t apply. EnumSet is nice. It is a type safe-way to work with a set of enums. The implementation uses a simple integer when the enum type has less than 64 members and a set for the uncommon case of more than 64 members. People build such a class for themselves with more or less quality.

Item 37: use EnumMap instead of ordinal indexing

[1/5] This doesn’t apply. We would just use the enum (class) as key of a container because an enum instance is a fully supported object in C++ while an enum in Java is like a primitive type, so the EnumMap workaround is needed. The split into objects and primitive types is the single most annoying issue in Java.

Item 38: Emulate extensible enums with interfaces

[5/5] Enums in C++ and Java have the same issue in that they are not extensible. This tip proposes to use static final objects and subclassing. This also sounds like the right design in C++. I could not find any core guideline talking about this topic.

Item 39: Prefer annotations to naming patterns

[1/5] C++ doesn’t have a direct equivalent technology to annotations. C++’s annotations have a similar purpose to Java’s annotations but are hardcoded into the compiler and are not extensible or queryable at runtime. Since there is no runtime reflection in C++, one cannot build ‘magic’ with naming patterns.

Item 40: Consistently use the Override annotation

[5/5] In C++, it is not an annotation, but a keyword, but this is still absolutely true. This is covered in core guideline C.128.

Item 41: Use marker interfaces to define types

[2/5] Marker interfaces in Java are actually quite similar to type traits. However, the details differ so much that I can only give 2 out of 5.

3 out of 8 apply.

Chapter 7: Lambdas and Streams

Java introduced Lambdas in Java 8 (in 2014). C++ introduced Lambdas in C++11.

Streams (also in Java 8) are quite similar to ranges in C++20. However, they also have some overlap with standard algorithms. My knowledge about ranges in C++ is just book-knowledge (or better YouTube talk knowledge).

In Java you can write:

v.stream().sorted(Collections.reverseOrder()).filter(Helper::isEven).forEach(System.out::println);

with the equivalent ranges code being:

for (auto const i : v

| rv::reverse

| rv::filter(is_even))

{

cout << i;

};

Java’s streams are more powerful than range as they have for example build

in grouping capabilities. And while there are parallel algorithms for the standard

algorithms, AFAIK there are not yet parallelism capabilities for ranges.

Item 42: Prefer lambdas to anonymous classes

[4/5] C++ doesn’t have anonymous classes (mostly), but the rephrasing would be “Prefer lambdas to callable classes”. So, this is true even when the details differ.

Item 43: Prefer method references to lambdas

[1/5] In C++ we have method pointers and method references, but we cannot just use them so easily instead of a lambda. So, this doesn’t apply.

In Java, you can write

String[] stringArray = { "Barbara", "James", "Mary", "John",

"Patricia", "Robert", "Michael", "Linda" };

Arrays.sort(stringArray, String::compareToIgnoreCase);

while you have to write in C++

std::sort(begin(v), end(v), [](auto const & a, auto const & b) {

return boost::iequals(a, b);

}

// std::sort(begin(v), end(v), boost::iequals(a, b); not possible

Item 44: Favor the user of standard functional interfaces

[4/5] This item is about using the standard functional interfaces like Predicate<T> instead of having a different type. This doesn’t apply nowadays in C++ as we use a template typename or std::function<bool(T)>. However, in C++20 this will start to apply

with concepts, e.g. ‘std::predicate’. I give it a 4 out of 5 because one shouldn’t go in and re-invent standard concepts.

Item 45; use streams judiciously

[4/5] While streams and ranges increase the readability and the level of abstraction. the tip warns that it is possible to overdo a good thing and sometimes a very long stream chain can become hard to read. As far as I can tell, the same is true

for long ranges chains.

Item 46: Prefer side-effect free functions in streams

[5/5] Again no streams, so this doesn’t apply directly. But it applies to lambdas provided to standard algorithms and ranges. This is especially important with the parallel standard algorithms of C++17.

Do not write:

vector<my_type> before_b;

auto i = std::find_if(begin(v), end(v), [&](my_type const & e) {

before_b.emplace_back(e);

return e.key == b;

});

There is no guideline about the topic.

Item 47: Prefer Collection to Stream as return type

[1/5] Does not apply to C++’s ranges. The output of a ranges chain

will feed into a ranged for loop (aka begin() and end() are available).

Item 48: Use caution when making streams parallel

[4/5] I will apply this tip to the parallel standard algorithms in C++17. I have used the parallel algorithms because they don’t mix well with Pure’s threading system, but from all I can tell, this applies.

From all I can tell, there are no core guidelines about the parallel standard algorithms at all.

2 out of 7.

Chapter 8: Methods

We have methods in C++, so a lot might apply.

Item 49: Check parameters for validity

[?/5] There the C++ practice appears to differ very much. The C++ standard library mostly doesn’t do it and declares a violation undefined behaviour. Pure Storage partially lives by this item. We have various kinds of assertions in our code base. Some only in debug mode, some also in release mode.

Item 50: Make define copies when needed

[5/5] This depends again on the reading. Value semantics are very much about defensive copies. When we return a container from an accessor method, we either return it by const reference or as a copy. This is a topic where C++ has much more elaborate tooling and guidelines than Java has. As in Java everything is a mutable reference by default, this tip is much more important in Java.

Item 51: Design method signatures carefully

[5/5] yes. Even the details of the tip match to 100%. The tip consists of many smaller guidelines like “Prefer two-element enum to boolean” which makes Abseil’s TotW 94. While different core guidelines, e.g. I.23 touch the topic, the coverage isn’t nearly as broad as in Effective Java.

Item 52: Use overloading judiciously

[3/5] Yes. Method overloading is more important to C++’s practice than to Java’s. The general discussion actually applies. The one safe policy for Java is to never have two overloads when they have the same number of arguments. That doesn’t appear like C++ to me. So, the arguments actually also apply, but C++ in general makes a slightly different tradeoff here. in C++, we think more in terms of overload sets.

Item 53: use varargs judiciously

[1/5] Java varargs sound similar to C’s varargs system that C++ inherited, but it is actually very different. It looks syntactically a lot like variadic templates, but they are like initializer lists.

The tip deals mostly how to enforce at least one parameter in the vararg list, which isn’t possibly nicely with initializer list, but would be possible with variadic templates where the type is limited with enable_if or static asserts. However, one of that is nice.

Item 54: return empty collection to arrays, not nulls

[2/5] A collection is returned by value in C++ all the time. So this item does not apply. You have to work really hard to design an example in C++, which wouldn’t be flagged in review immediately. So, in theory, this applies, but it applies trivially.

Item 55: Return optionals judiciously

[3/5] Optional is very similar to std::optional, but it might surprise you. In its argumentation, the tip doesn’t really apply to std::optional in any way. I give this 0 of 5. This is surprising, the same name used for the same reason, but the tip doesn’t apply.

Abseil’s tip 163 about optional and why

it is likely not a good idea to use optional to pass parameters to a function and

that the likely best use-case is to return values. This matches the Java guidelines.

Most of the explanation applies to C++. However, not all of it, e.g. the boxed primitive discussion doesn’t apply to C++ at all.

[4/5] I don’t know about other people’s C++ code, but my impression is that C++ programmers should be much better at documenting invariants and assumptions. Even taking Hyrum’s law into account. Maybe Hyrum’s law in a thing in the C++ world because the separation between the interface and the implementation is so much weaker than in the Java world and the documentation is often worse. People code against an implementation because they don’t have a choice.

4 out of 8 apply.

Chapter 9: General programming

One would assume that most tips about general programming would be applicable. We will see.

Item 57: Minimize the scope of locals

[5/5] Yes. Please do so. Interestingly and especially because C usage is still very different here, I could not find a guideline entry about this. The nearest I could find is NR.1, which is sorted under “Non-Rules/Mysts”.

Item 58: Prefer for-each loops to traditional for loops

[5/5] C++ calls them ranged-for loops, but even the syntax is identical. So, this applies to C++, maybe with the additional hint that one should consider replacing the ranged for loop with a standard algorithm if applicable. Or ranges.

Item 59: Know and use the libraries

[5/5] The Java standard library is way more extensive than the C++ standard library, but the tip still applies. Item 54 and 55 of Effective C++ cover it as do SL.1 and SL.2 of the core guidelines.

Item 60: Avoid float and double if exact answers are required

[5/5] Both languages use IEEE floating-point semantics, so this applies to both languages. Surprisingly, I cannot find a guideline about this.

Item 61: Prefer primitive types to boxed primitives

[1/5] The difference between primitive types and boxed types is one of the worst elements of Java. In C++, thankfully, almost everything is an object (in C++’s sense of an object) and there is no difference.

Item 62: Avoid strings when other types are more appropriate

[5/5] Yeap.

[5/5] We can have a discussion in which language the normal performance of trivial string concatenation is worse. C++ has a slight advantage as we can reserve on a string and update the string in place, but stringstream is often a better idea especially when conversions are involved and in Java it is StringBuilder.

I cannot find a matching guideline in C++. However, Abseil TotW/3 talks about string concatenation.

Item 64: Refer to objects by their interface

[5/5] Java developers make a much better job in general to specific interfaces and contracts and code against interfaces instead of implementations, but just because C++ often doesn’t do a good job here doesn’t make the tip wrong.

Item 65: Prefer interfaces to reflection

[1/5] C++ doesn’t have reflection at this point.

Item 66: use native methods judiciously

[1/5] Does not apply to C++. Maybe I can find extern "C" functions are the C++ equivalent to native methods, but that would be a stretch.

Item 67: Optimize judiciously

[4/5] While C++ code has higher performance requirements (why otherwise would we use C++ in the first place), there is a lot of premature optimization going in C++ code. When reading the more detailed tips of this article, it mostly applies to C++, too.

Item 68: Adhere to generally accepted naming conventions

[1/5] C++ have not generally accepted naming conventions which one could adhere, too.

C++ developers can’t even agree if const comes left or right of the decayed type. The right answer is right BTW. The nearest match is NL.8, which recommends to at least have a consistent naming convention in house.

Chapter 10: Exceptions

The exception system in Java and C++ works quite differently. And I have to emit that I never in the last 20 years coded in a C++ codebase with used exceptions (not a joke), so my knowledge in this topic is a bit hazy.

Item 69: use exceptions only for exceptional conditions

[5/5] True. E.3 recommends “Use exceptions for error handling only”.

Item 70: Use checked exceptions for recoverable conditions and runtime exceptions for programming errors

[1/5] I always liked Java model and I might be the only one. I think a lot of people got it taught incorrectly and in the early days of the Java design (Java 1.0, Java 1.1) a lot of mistakes were made, which never could be corrected anymore. However, this doesn’t apply as C++ doesn’t have the difference. In a sense, all C++ exceptions are equivalent to Java’s runtime exceptions. The last leftover of checked exceptions, the throw exception specification, has been removed in C++14.

Item 71: Avoid unnecessary use of checked exceptions

[1/5] C++ doesn’t have checked exceptions. Thus, this doesn’t apply.

Item 72: Favor the use of standard exceptions

[?/5] C++ has only a very limited list of standard exceptions. I honestly do not know if this applies to C++ or not. As far as I can tell, there are not standard exceptions in C++.

Item 73: Throw exceptions appropriate to the abstraction

[5/5] I assume this also applies to C++. Don’t throw a http_exception out of your SQL client library when sql_connection_exception would be more appropriate. No guideline about the topic.

Item 74: Document all exceptions thrown by each method

[5/5] I wish C++ would do this. The standard library does, e.g. std::vector::at, but who else?

[1/5] As far as I know, this doesn’t apply to C++ exceptions.

Item 76: Strive for failure atomicity

[5/5] Complete books (or at least sections of books) are written about this in C++ and there are multiple levels of exception safety in C++. It is getting complicated quite quickly in C++ as you have no idea where which exception might be thrown. Item 29 of Effective C++ recommends “Strive for exception safe-code”. Surprisingly, there is nothing in the core guidelines about this.

Item 77: Don’t ignore exceptions

[5/5] Still applies. No guideline about the topic.

Chapter 11: Concurrency

In C++11, C++ introduced a memory model, which was more or less taken over directly from Java 5 (introduced in 2004).

Item 78: Synchronize access to shared data

[4/5] This is even more important in C++11. Data races are undefined behaviour. CP.2 says “Avoid data races”. There is nothing in Effective Modern C++ about data races and Effective C++ is not able to talk about data races because C++ didn’t know what concurrency is when the book was written.

However, the details are different. C++ doesn’t have synchronized build into the language. Java’s volatile has a very well defined and useful meaning for concurrency in contrast to volatile in C++. So I reduced a point.

Item 79: Avoid excessive synchronization

[5/5] True. Knowing, my performance-obsessed C++ developers, data races are often the bigger problem than excessive locking.

Item 80: Prefer executors, tasks, and streams to threads

[1/5] We are not there yet in C++. Java 1 already had threading support. Java 5 added the executor framework. Java 7 the fork/join framework. Multithreading support in Java is really nice. The standard library support in C++ is still much more rudimentary. I hear executors might make it in C++23.

Item 81: Prefer concurrency utilities to wait and notify

[1/5] In Java, each object has a build-in condition variable. What this tip is about is to prefer using higher-level tools like ConcurrentHashMap (no equivalent in C++), BlockingQueue (no equivalent in C++), CountDownLatch, and so on instead of the low level wait/notify mechanism. The Java concurrency library is really great.

C++ has mutex and condition variables as extra classes as Java has since Java 5 and that is essentially it. C++’s concurrency tools are effectively at the level of Java 1.0.

Item 82: Documentation thread safety

[5/5] I already lamented that C++ engineers should do a better job documenting. This stays true for documenting thread safety.

Item 83: use lazy initialization judiciously

[4/5] Lazy initialization is a bit more important in C++ because static initialization order between translation is undefined while it is defined in Java. However, constinit makes the situation a bit better. In C++, we don’t have to use the double-check idiom. The language does it for us.

Item 84: Don’t depend on the thread scheduler

[5/5] I have seen too much code which tried to fix concurrency issues by randomly adding sleeps or yields. Just do not depend on the thread scheduler.

Chapter 12: Serialization

Java’s built-in serialization system is a mess. I expect that no item is applicable.

Item 85: Prefer alternatives to Java serialization

[1/5] Should be obvious why

Item 86: Implement Serialization with great caution

[1/5] Does not apply

[1/5] Does not apply

Item 88: Write readObject methods defensively

[1/5] Does not apply

Item 89: For instance control, prefer enum types to readResolve

[1/5] Does not apply

Item 90: Consider serialization proxies instead of serialized instances

[1/5] Does not apply

Yes, 0 of 6 apply. Honestly, the framework is so broken, the chapter should be condensed to “Don’t use it. Ever”.

Summary

Many tips from Effective Java apply more or less directory to C++ code. There

is only a single instance where a reader would be actively misled by reading

this book about Java (about finalize and RAII).

In addition, many important tips that apply are not covered by the guideline books.

Many are only covered by the core guidelines. However, since the core guidelines

have many hundreds of tips (see core), you need a lot of stamina to actually read throw it. That there is a large overhead with issues mentioned in the core guidelines prove my point that there is a lot over

the similarity between the language.

The short books we can hand to junior engineers and new hires, only cover a small subset

of the items, which apply from Effective Java. I would like to hand them Effective Java

in addition to Effective Modern C++ and Effective C++.